Seat 45: My Vipassana experience

In September 2018, with 32 years old, single and after having worked for tech startups in London for four years, I decided to sign up for a silent meditation retreat in Chennai, the capital of the Tamil Nadu region in the South West of India.

Bangalore, India, October 2018.

Sunny and I stepped out of the packed train in Bangalore after a hot seven hour ride through the southern Indian countryside. We’re greeted by screaming vehicle horns, motorized rickshaw squeezing through the traffic, the chaos and the crowd. No matter how happy I was to be back in Bangalore after the emotional roller coaster of the last few weeks, that busy intersection outside the station was still a daunting sight for me. Standing on my right Sunny sighs in relief. For him this was home.

That train ride to Bangalore ended a two week trip to Chennai where I did my Vipassana course. There I met Sunny, a soft spoken handsome young Indian man and Inga, a life loving German artist that had just relocated to Bangalore. The three of us made the trip in an Indian Express train that got so full of people that at some point I couldn’t stand up in the aisle and had Inga climbing on my back to allow passengers to leave the window seat.

We spent ten days at the centre in an old rice field in the hot and humid capital of Tamil Nadu, practising meditation ten hours a day from 4:30 am to 9:30 pm, with breaks for meals and short walks. This article is my account of that course. If at least one person resonates with what I’ve written and finds that the course could be potentially helpful then it was worth the time. I’ve tried to be as considerate as possible with my descriptions, especially as I talk a lot about moods and what was going through my mind at the time. We weren’t allowed to have writing materials during the course but I started taking notes as soon as I was able to put pen to paper. In fact, as I was going through them a few months later to write this, some of them were a surprise even to me and I wouldn’t have been able to remember things had I not done so. This was even more so for notes relating to my internal mental states as people and places, curiously, are always easier to remember.

If you’re signing up for a Vipassana retreat looking for a relaxing meditation experience, then you won’t find it here. Vipassana is not about the pursuit of any given desirable mental state. Rather it’s about observing and accepting what’s already there in consciousness, pleasant or not. It’s not the type of meditation experience you’d find in a music festival or the Fabric*. It’s about hard work, discipline and sitting equanimously, a word I had to look up, through a lot of uncomfortable hours.

In Vipassana, by sitting through the aches and pains of standing still for long hours, observing the coming and going of body sensations you learn, at the experiential level, that your misery is temporary. Through practice and hard work you’ll learn to deal with feelings of aversion, training your mind not to get carried away by whatever undesired feeling or thought that pops up in your head. Ultimately, you’ll feel more relaxed, but that is a consequence of being undisturbed and no longer reacting unconsciously to cravings and aversions.

The idea that happiness should be unconditional, that you choose to be happy regardless of the external conditions and that misery is the result of how you take things, rather than the things themselves, is a very Buddhist notion and one in which a lot of people find solace. However, the course, coming from a Buddhist tradition, distinguishes itself from other meditation schools by the emphasis in the experimental practice. At the centre you won’t find Buddha statues, there’s no chanting, no incense burning and no rituals to do.

Anapanna and Vipassana

Before going into Vipassana, you’ll learn another meditation technique in the first three days called Anapanna. The procedure is simple: eyes closed, sitting upright with legs crossed, focus on the triangular area formed by the nose and the area between the nose and the upper lip. The exercise is to observe this area for sensations that arise while breathing, while avoiding trying to control it. Also, there’s no counting, chanting or visualisation. Although all of these help to focus, the exercise is to focus on the breathing and body sensations only.

On the fourth day you’ll start doing Vipassana. Now, instead of observing just the breathing, you’ll observe sensations throughout the body. Starting at the top of the head and scanning downwards, first the scalp, then the face and back of the head, right arm, left arm, throat, chest, neck, back and legs. Scan for different sensations like heat, perspiration, itching, pulsating, etc. You’ll start picking up the same type of sensations and working towards a full body scan in one go.

And this is all there is to it. No chanting, no visualization, no counting, no complicated foot position. The job is to observe sensations and realise that these arise and disappear in consciousness. By not reacting with aversion and sitting through your practice, just observing all the uncomfortable sensations going through your body, you’re training your mind to understand that pain is temporary. You are also told not to make it worse than it already is; not to torture yourself. Take breaks if you have to or use more cushions. However, the discomfort actually helps with meditation. If you’re too comfortable you’ll start feeling sleepy during the long practice and struggle to remain aware. The brutality of the practice has the added effect of pushing you into meditation, as you quickly understand that the hours meditating are actually pleasant and you reach a certain state where the pain is there but it doesn’t bother you.

From the beginning, you start a process of negotiating with yourself the long hours. My strategy was to tell myself that I was going to be a poor meditator until I actually became a good one. Soon I found that perfectionism was indeed a discomfort I had some control over. Working my way up, I tried to remain as still as possible from day one. First five minutes, but no more. Then ten, twenty, thirty. By day three I was able to sit through pain and discomfort for one hour without changing my posture.

If this looks total sadomasochism to you, just keep in mind that the end game of the practice is to make you able to cope with discomfort in life (remember equanimity?). For that, you literally sit for painful lengthy periods at a time, until effectively, you’re ok with it. In this way if there’s no discomfort there’s nothing to remain equanimous against.

Dhamma Setu

The Dhamma Setu Vipassana Centre is located in an old rice field about 10 km from the Chennai International Airport. You can see the aeroplanes landing every 15 minutes and cows roaming around, providing the occasional after meal interaction. Some would even stay patiently outside the dinning hall waiting to be fed papaya skins and other leftovers.

The main meditation hall is a one floor building with white wooden boards decorating the walkway roof and palm trees surrounding the main gardens. Tall trees flank the walking areas and provide shadow and relief. The gardens are incredibly well groomed and the walking areas are meticulously raked in the morning and evening.

There are Vipassana centres in the UK that offer good accommodations in Suffolk and Herefordshire, both a few hours on a train from London where I currently live. I chose to do it in India however, as part of a long overdue visit to my friend Hugo from Engineering School, that had moved to Bangalore two years ago. I could have done it in the UK, and I’m sure the experience would have been just as valuable, but I just couldn’t imagine myself saying to someone that “my spiritual awakening had begun with a Thameslink ride to Suffolk”.

With little time to plan and my flight date approaching in less than a month, I looked into the Bangalore Vipassana Centre but it was fully booked for the following months. Later I found that this is usually the case as these courses are well sought after in some areas. Facing the Indian Ocean and six hours away by train, Chennai seemed like a good alternative. I knew nothing about the city at that point, but was willing to make it my personal Finis Terræ.**

The men’s meditation hall and the immaculate main garden of the Dhamma Setu Centre.

The men’s meditation hall and the immaculate main garden of the Dhamma Setu Centre.

Journey Begins

As a disclaimer about where I stand in the spirituality spectrum, I’ll share a funny personal story. I already considered myself a sceptic and non-believer in my early twenties when a friend decided to pull a prank on a few of us in an abandoned hospital, complete with a video recording that revealed ghostly children voices warning us not to come back. What little doubt I had in me was stirred a bit only to be quenched when the prank was revealed. That single episode made me understand at an experiential level, how easy it is to hold on to beliefs for which there’s little to no evidence and to value a way of thinking that left little room for spirituality.

I saw with great scepticism if not downright cynicism, the guru who spoke of aphorisms as I always approached people dispensing life advice for a living with caution. It seemed clear to me that a mystical layer on top created a dangerous mix of authority and obfuscation. As I kept myself away from the traditional vessels of meditation, it was an interest in cognitive science in fact that rescued this practice from spirituality for me. Consciousness captured my curiosity from about the moment I started working in software and Meditation is one tool used to poke at the elusive nature of the mind.

After almost 4 years of working for tech startups in London I, at the time a 32 year old single guy, found myself thinking that the best thing to do was to get locked in a meditation centre for 10 days straight with no communication to the outside world. I was considerably burned out and had flirted with meditation in the past to know that it would benefit me. I had done my own research and tried out the apps but finally, it was Jodi Ettemberg gruelling account of her Vipassana course and knowing that Yuval Harari was a Vipassana meditator that convinced me to sign up for the course. In this way, I find myself travelling through the southern parts of India playing the role of the seeker.

It wasn’t a comfortable journey which was just fine for me. Bangalore is equal parts rich and chaotic and Chennai is not catered to European standards of comfort. Traffic is busy, and there’s a broken water treatment system that can’t cope with the population density making some parts of the city smell really bad. Europeans should not fear the lack of western style toilets, as this will be the least of your concerns. I found kindness and was welcomed by total strangers in an uncommon way to some parts of the world, like when I was having a coffee waiting for my taxi to the Vipassana centre. I sat in a crammed breakfast house and placed my coffee a bit too far to the edge of the table. While I was finding a place to put my bag in the floor, the guy sitting in front of me, jumping over any considerations of personal space but making me feel welcomed nonetheless, simply moved the coffee cup towards the centre to avoid any spilling and slowly nodded at me.

I showed up at the centre one day before the course started as instructed. I got there around 3 pm, signed up, dropped my mobile and books in a box and then we had a small meal in the dining hall where the course rules were laid out: we were not allowed to speak, we had to abstain from killing, talking, sexual activities and lying. We had to stay for the whole duration of the course. We were told that if we didn’t agree with the rules then we should leave. Afterwards, the course was split into men and women for the whole duration and we were called into the meditation hall for our first evening sitting. I stepped into the meditation hall where some of the students were already sitting, the first couple of rows having old students only.

We had a light blue cushion of about 60 cm by 60 cm where we could fit cross legged. Additionally, we had a smaller 5 cm height cushion where we actually sat, which gave some support for our backs. I sat there recalling the discomfort of my past meditation attempts thinking how I was going to pull off an hour of sitting there, let alone ten days. I looked around and started counting the number of cushions. Nine rows of ten cushions each make 90 seats. Mine was number 45. Shortly after everyone is seated, the first meditation session of day zero starts.

I found myself thinking that all was going well with my meditation 25 minutes into it, shifting to the realization that I had 100 hours of that in front of me. I felt trapped and had a sudden urge to twitch my body just to prove I could still do it. Next I had to fend off a sudden desire to storm away from the hall. I couldn’t quite understand where all that anxiety and dread was flooding from when I realized I was having a panic attack and had to talk myself through it. I said to myself “you’re having a panic attack, you’re free to go anywhere, you’re not trapped. You knew this was going to be hard, this is it, this is the challenge, this is the hard bit that you have to overcome, right here.” A strategy I soon learned when I started doing Brazilian Jiu Jitsu and that I carried over outside the mats. I was already an adult and I remember quite well being overwhelmed and the feelings of hopelessness. A man 40 kg heavier on top of you, smothering you, choking you. I remember having to talk myself through some of those earlier sessions, reminding me not to tap under pressure. That it was a sport and it would all be over in five minutes. Your body reacts with panic to this type of pressure, but soon you learn that you can always find some space to breathe. There’s always a tiny place you can find to allow your nose and mouth to grasp some air. There’s always something you can do other than dying. Now in a meditation hall, considering each moment born as a small victory, talking myself through the process, trying to hold still, creating small goals, telling myself that I was free to move, to readjust my position at any time. Perfectionism wasn’t an issue I was willing to deal with.

Our spartan accommodations for the 10 days, comprised of two beds and a bathroom, complete with waking up service at 4:00 am.

Our spartan accommodations for the 10 days, comprised of two beds and a bathroom, complete with waking up service at 4:00 am.

The hour session ended and soon we went to our rooms. It was the beginning of the monsoon season and the room felt like a green house although the sun had set a while ago. I was later told I was lucky and had come at the right time: during the summer days the heat is way harsher.

We couldn’t keep books or note pads but I had a piece of paper, a label from a dhoti (a rectangular piece of cloth that men traditionally wear around the waist,) which I had bought with the help of one of the volunteers. I used it to keep track of my mood through the days by making small indentures on the side of the label, the length of each showing how I felt relatively to the day before. I did this as I wasn’t neglecting the possibility of going down a paranoid rabbit hole by losing track of time.

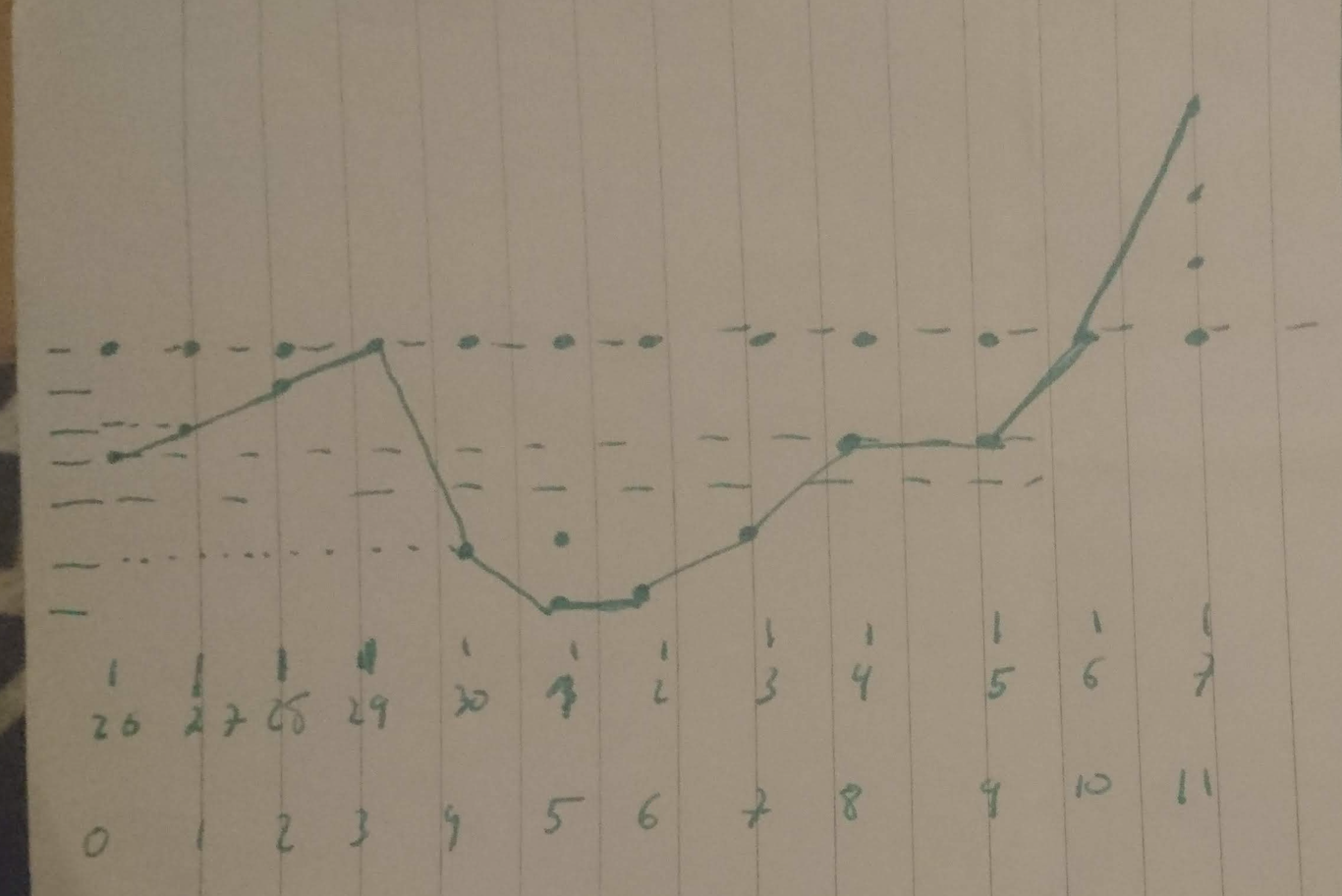

I made a graph from the indentures on the label. The idea here was to have an “absolute” value for my mood, tracking only my perception of how I felt relatively to the previous day. Variations in scale can be interpreted like — a bit more or less anxiety than the previous day: 1 “unit”; a stronger variation: 2 units; panic attacks: 3 units. First row of numbers are the days, from the 26th of September to the 7th of October. Day one is when the course actually started and day zero is the day before, when I had my panic attack during the first sitting. The markings on the left are my mood scale and needless to say, it’s as subjective as it comes. Day zero is three “units” worst than the day before (to account for the panic attack.) Day one was a bit better but still pretty miserable. Day three I felt as good as the day before the course. Day four is when I got sick and day five I hit my lowest mood. Things to note: during the course, my mood was always worst than before the course. Getting better was always slower than getting worst. Leaving the centre had a symmetric effect to the panic attack in the beginning.

I made a graph from the indentures on the label. The idea here was to have an “absolute” value for my mood, tracking only my perception of how I felt relatively to the previous day. Variations in scale can be interpreted like — a bit more or less anxiety than the previous day: 1 “unit”; a stronger variation: 2 units; panic attacks: 3 units. First row of numbers are the days, from the 26th of September to the 7th of October. Day one is when the course actually started and day zero is the day before, when I had my panic attack during the first sitting. The markings on the left are my mood scale and needless to say, it’s as subjective as it comes. Day zero is three “units” worst than the day before (to account for the panic attack.) Day one was a bit better but still pretty miserable. Day three I felt as good as the day before the course. Day four is when I got sick and day five I hit my lowest mood. Things to note: during the course, my mood was always worst than before the course. Getting better was always slower than getting worst. Leaving the centre had a symmetric effect to the panic attack in the beginning.

I had a cold shower to cope with the heat and set my ceiling fan on max. I went to bed and laid there getting psychologically ready for the 4 am waking up call.

First couple of days were sore but manageable. You quickly get into the routine and understand what the exercise is all about. We were allowed to use more pillows to ease the discomfort of sitting but I chose not to as I wasn’t ready to face the possibility of realising that more pillows didn’t improve my misery that much. I just chose to have the pillows as a comfort option.

There was a sand coloured gecko in my bathroom which I named Bob. I would see Bob in the middle of the night when I would go for a cold shower to help me sleep. Bob wasn’t used to being interrupted in the middle of the night so that’s when he went about to do his business. I say “he” as we were in the men’s quarters after all. Around the third night Bob had enough of being surprised; he was midway the bathroom wall when he drops with a loud “thump” and runs to the back of the toilet not to be seen again. He had had enough of my erratic schedule and couldn’t wait to have a more acclimatized room mate.

Things were going well and by day three I was already able to sit one hour without twitching a muscle. Sore legs and back stopped being an issue and I was really happy with the progress. On the fourth day, a mixture of tropical weather, stress and sleeping with a fan in the maximum setting, gave me a bad case of tonsillitis and fever. Things got so miserable that I would have given up if I were a train ride from home. Just thinking about the trip back, made me realise that for all its aches and pains I had food and shelter.

Thoughts of quitting got really persistent at this point. Running away would have been easy. We could see the main gate during our walking routine, it was always wide open during the day and leaving would have taken five minutes. I fantasized many times about doing so. I kept negotiating with myself that all I had to do was just focus on bearing each moment. I kept recalling moments when I felt as miserable as this; a good comparison was when I got ill with meningitis at the age of 19, not being able to sleep more than half an hour at the time for two weeks unless I was heavily sedated. The staff at the centre were really helpful. They told me not to quite and to hang on, they gave me a chair, paracetamol and told me to skip the morning 4:30am meditation for a couple of days.

This is a specially poorly lit photograph but it’s the only one I’ve got from the meditation hall. Plain white walls and at the front you’ll find the teacher’s chairs and sound equipment. Of the nine rows of cushions, only six are left. The picture is not mine but ended up in my Whatsapp folder somehow and I’m hoping the owner won’t mind me reproducing it here.

This is a specially poorly lit photograph but it’s the only one I’ve got from the meditation hall. Plain white walls and at the front you’ll find the teacher’s chairs and sound equipment. Of the nine rows of cushions, only six are left. The picture is not mine but ended up in my Whatsapp folder somehow and I’m hoping the owner won’t mind me reproducing it here.

I would have left if that were the option that maximized my wellbeing. I was short of considering that experience as hell, which I didn’t as I could see there was a meaning to it. Coincidently, although I wasn’t in the right shape to practice the technique itself, my overall discomfort helped me to understand the point of the course. I started shifting my mind set from self-pitying thoughts and frustration, towards observing and acceptance.

Fever makes it hard to focus and you’ll find yourself hallucinating when meditating. Usually, the practice is to bring your attention back from a distracting thought to the breathing or body sensations. With fever however, the thoughts that slip through surround you in such a way that you find yourself having to bring your awareness to a different reality and that effort is really unsettling.

The film Jacob’s Ladder started popping in my head until day seven or eight. I felt that if there was a purgatory, sitting through that level of pain would be it. Not sure to what degree I believed in that, but I found myself reconstructing my journey to the centre, making sure every airplane had landed, every train and cab ride had ended safely.

After day eight my mood started to get better. Still, there were moments I felt trapped and wanted to run away. It’s not that these moments were more bearable, it’s just that now somehow I had the strength to bear them.

Day ten, noble silence stops and we start chatting and exchanging impressions. I notice that speaking is an ordeal now. Anything other than expressing immediate thoughts flow only with great effort. The rest of the students wonder about what had brought me to Chennai; if there was corruption in my country and whether I was married. We would stand in circles and throw questions at each other. We resumed conversations that we had left and commented on the ones that had quit. Looking at the missing cushions, we estimated around 20 guys had quit. Three rows of ten were gone, but some chairs were scattered around the back of the hall.

We exchanged life experiences and the motivations behind the course. Some were spiritual, some are rooted in really difficult life circumstances. The sittings are still segregated but some parts of the centre are now open to both genders. Long duration silent suffering seems again to be a female speciality. Heartbreaking stories of women trapped in abusive marriages, with no work and kids involved. For all it’s aches and pains, this retreat was relief for some.

Day 11, I felt ready for London, so much so that I started looking at flights back and wanted to shorten my trip by almost a week. There was work to do back home. Reaching Bangalore changed my mind and I’m glad I stayed a few more days. Unlike some other retreat reports I had read, I didn’t feel like staying. I was ready to go and never to do this again. Needless to say, a few weeks after being back in London and the idea that a student could return and repeat the course started to feel less and less strange.

Course was over, pictures were taken.

Course was over, pictures were taken.

I remember quite distinctly my state of mind after the course. Time slows down and the contents of your mind become more clear. I remember looking at my mobile and at all the notifications and, although I felt the need to reply to each one of them and tell people back home that everything was ok, I didn’t feel the urgency and restlessness that comes with a full email box and 150 notifications in your messaging apps.

A couple of weeks after, I wrote in my notes “it’s like a shroud has been lifted and I see things without this filter of sadness and worry. Before I used to feel anxious, overwhelmed every time I remembered all the things I still had to do, now, I feel energized by them.”

Perhaps, part of me feeling so much better is because of having completed a deeply meaningful, extremely hard trial. The kind of experience that humans thrive upon and are so rare today.

Another insight that I had later when I was already in London, was that when you come across a problem in your mind, the reason it gets stressful might be because you don’t have a solution for it first. Refocusing your attention at the task at hand lets you revisit the problem later on when you might have a solution for it. That’s just the way the brain works, it seems. Having a solution for a problematic thought makes it less so, therefore, less stress.

A frequent question I got about the course when I came back was simply if I had managed to meditate. At first, the question felt weird for a few seconds until I managed to articulate why. What you soon realize in the course is that just being present in the meditation hall, sitting down on your cushion and trying to meditate, is meditating. Making the effort of bringing your attention back to your breathing is the point of the exercise and every time you are doing it, you are training your mind to be more focused and disciplined.

You are sitting down cross legged, eyes closed, focusing on your breathing and a buzzing pain has settled on your lower back. You realise that your mind starts to wonder. Thoughts pop up in consciousness and you get carried away by them. Usually, they’re not pleasant and you’ll find yourself dealing with many things that have been haunting you and you realise that all your problems and worries followed you. At this point, if you don’t get the point of the practice, it will be very difficult to continue and you will quit.

You recall all the circumstances when you couldn’t bring yourself to do something despite knowing it was in your best interest, either because you were too tired or too uncomfortable. When you knew that you didn’t have much choice but to endure the situation and to continue doing the work because it was the only way out of that mess.

For instance, I recalled working on my dissertation and despite the fact that my scholarship was coming to an end and I was going to be in dire financial difficulties unable to pay rent, I found it extremely hard to stay focused and finish the manuscript. Sure that was a tumultuous period when I moved out of my parents’ house under unfortunate circumstances and moved into a flat in a relationship that was every bit as tumultuous as the place I had left. But, those were the circumstances I had gotten myself into and despite the fact that I was beyond exhausted, not finishing the work and moving on to the job market would put me in a much worse place.

Or when I found myself in a failed business venture, with no financial support to take entrepreneurial risks and with a massive workload on my shoulders. Every fibre of my body screaming for that to stop and the end of the month fast approaching. The ability to deal with extreme feelings of aversion and remaining focused on the task at hand would have been much appreciated.

You recall these moments and you understand the purpose of the practice and that had you had the skills you were practising that very moment, things would have been different. So, in respect for those moments, you can’t just bring yourself to get up and leave.

No western therapist would bring him or herself to subject you to endure such level of adversity and yet, training the mind requires just that. Quit smoking, waking up on time, changing behaviours that you know are causing you harm but you can’t bring yourself to do it. Cognitive behavioural therapy teaches you how to identify false beliefs and break away from patterns of behaviour that are bad for you. Literally, things you’re doing to yourself that cause you harm. However, it tells you absolutely nothing on how to maneuver across the negative state of mind that comes with changing behaviours that you already know are bad. When you can’t resist the craving of one more cigarette or when you can’t sit down to do the things you have to do and everything seems to want to distract you.

The very fact that therapists avoid the term patient, common in clinical practice, and use the term client instead, says how little they are willing to subject a person to any uncomfortable situation, albeit being in their best interest.

Bangalore Express

Sunny, Inga and I being tourists in front of the Vidhana Soudha, Bangalore.

Sunny, Inga and I being tourists in front of the Vidhana Soudha, Bangalore.

With an airplane return ticket in my hand, I ditched the predictable comfort of a modern airliner for one final adventure with my two new friends I made at the course, Inga and Sunny. As it turned out, both were serious meditators, as they sat for ten days with only one of the smaller cushions. In meditation terms, this means you’re hard and mean.

The fast train was already fully booked which left us the option of a third class Indian Express ticket, with an estimated travel time of around 7 hours. Air conditioning was not part of the deal. We boarded the train around 1 pm, for the total cost of around 100 rupees, approximately 1£.

Negotiating our seats with fellow passengers we skipped between seats until we found a place for us to stay relatively close to each other. The train had been heavily overbooked which became more and more apparent as we approached the state of Karnataka. At some point movement became impossible, Inga having to jump on my back to allow a fellow passenger to leave the train. The ticket supervisor after trying to maintain posture over many hours, finally gave in to Inga’s charm, and shrugging confessed: “There’s nothing I can do, they overbooked the train.” He kept the appearance as long as he could. Despite its inconveniences, it was truly a fun ride.

The Indian countryside passing through the moving train with it’s green, wide open fields and palm trees. The wagon had a fully functional door and it was able to stay shut, but no one found the need to close it as it seemed. We had fresh food on board, coffee and tea. My favourite thing, I learned, was Gobi Manchurian, a delicious battered fried cauliflower with curry leaves. A vendor passed every 20 min or so. Best train service I ever had. Other passengers were extremely friendly. A random Indian guy started speaking fluent German with Inga. He had never been to Germany, learning the language was just a hobby of his.

Finally, we reached our destination. Inga still had a couple of stops but Sunny and I stepped out of the train into the main street. Sunny sighed in relief for being in Bangalore, his current city. As happy as I was for being out of Chennai, the transit and the pollution, relief was something I wasn’t feeling in that busy, noisy and chaotic intersection.

That night I returned to my friend Hugo’s place. Telmo, another friend from Uni, had joined him while I was in Chennai. What some would consider divine intervention, he had brought a few bottles of Portuguese wine on the plane with him that we polished off over dinner. Never the nostalgic type, I had a lot of trouble recollecting a better wine than the one I was enjoying at that moment.

Fast forward a few days of tourist affairs, shopping and the obligatory tourist traps, it was time to go home. On the day of my departure I had to leave Hugo’s place around 3am for my early morning flight. He had to call a cab for me as I was unable to get a SIM card during my stay, so none of us wanted to fall too deeply into sleep. We slept on the floor of his spacious living room, in a carpet that felt every bit as comfortable as the bed I had in Chennai. A peaceful sleep, with an early flight, lights, the sound of another human by my side. I wouldn’t have managed this just 3 weeks before.

Posing in front of what it seems to be a Brutalist building in Bangalore.

Posing in front of what it seems to be a Brutalist building in Bangalore.

A thank you note to Hugo, Angelina, Nilesh and Piyush for the hospitality, Alex, Anja, Giulia, Lena and Nima for helping me revise the tangled mess my early draft was.

Dedicated to all the kind people I met at the course.

* The Fabric is a well known electronic music venue in London. In May 2018 it hosted a group sitting for the World Meditation Day